Sharon Smith started working in Student Intervention Services in the aftermath of 9/11. It was the onset of the fall semester, and almost 3,000 people died in the attacks. Others were reported missing. It was almost impossible to secure a flight. In the aftermath of chaos, confusion, and grief, the Office of the Provost wanted to respond in a comprehensive way to students in distress, Smith says. With the support of Vice Provost Valarie Swain-Cade McCoullum, Smith worked with a small group of volunteers to be on call 24/7 for students needing help.

“What we found is that once a critical incident occurred, we needed postvention, if you will,” Smith says, “time to support the students after something large or major had happened that will impact our students. So that’s how we started.”

Formerly the executive director of Student Intervention Services, Smith is now associate vice provost for University Life. Student Intervention Services (SIS), the office she founded, is now a national model with four full-time staff members, plus the assistance of a shared administrative assistant. The office has what Smith calls “a multi-disciplinary approach,” partnering with the Chaplain’s Office, Student Health and Counseling, Financial Aid, College Houses & Academic Services, Penn First Plus, and the Division of Public Safety, along with the University’s 12 schools. The office responds to a range of student needs, from participating in well-being checks to booking flights to helping students dress for job interviews.

SIS identifies and meets student’s most urgent needs, Smith says. When a pattern emerges, like when students go from bringing a pen and notebook to class to taking notes on personal laptops, SIS works to formalize partnerships with other offices to anticipate the shift. “I like to demonstrate a need and then get commitment from the University,” Smith says.

“We don’t throw Band-Aids at the problem,” says Elaine Varas, senior university director of Student Financial Aid, who is frequently in partnership with the SIS office. “We’re creating a plan that helps students succeed at Penn.”

In 2017, SIS received a class gift to establish the University Life access and retention fund. Smith used part of that funding to purchase 40 laptops. The next year, the office began partnering with financial aid, which now provides laptops for all highly aided students. On top of that, SIS provides additional laptops for students through the emergency and opportunity funding program, which serves as a safety-net to make sure students don’t fall through the cracks. “Sometimes students are not defined as highly aided; that doesn’t necessarily mean that they have the means to get everything they need,” Smith says.

Many of the questions Smith asks are the questions she wished someone had asked her in college, she says. “I was a first-generation student and myself an immigrant,” she says. “I came here as a teenager from Jamaica with my dad and siblings, finished high school here the in U.S., and went on to college.” Smith attended Cheltenham High School in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, where in a student body of 500, she was one of six Black students. When asked what that experience was like, Smith paused. “It prepared me for the world,” she says.

Smith uses her experience to help vulnerable students at Penn, building SIS from the ground up. The program is a way for her to design the kinds of support she would have wanted as a young student, the support she helped to create for her younger siblings. “Our job is to create a safe space,” Smith says.

During the onset of COVID-19, SIS was part of the team that helped to depopulate campus, ensuring that students had a safe way to travel and a safe place to land. “With the pandemic, what stands out to me is the volume and the breadth of the impact,” says Lauren Rudick, director of SIS. “We worked with hundreds of students.”

Penn asked the team to pool their knowledge about students: Who could safely go home and sustainably study and who needed to stay on campus, says Varas. “It gives a holistic picture about a student,” she says. “Every one of us knows a piece, and when you put all the pieces together, it finishes the puzzle.”

“When you ask students to depopulate, what does it mean to a student who is highly aided?” Smith asks. For many, funding for housing and meals are crucial, she says. “Going home, those things might be a challenge. That’s where we come in, to be the advocate and the resource on behalf of the students.”

The fall of 2020 was an online semester, with students Zooming in from across in the globe. During the Africana Studies Summer Institute, professors noted that several pre-freshman students did not have their own laptops and were calling in on borrowed equipment or using their phones. “How do we admit students to a program that’s virtual, and they need equipment, and we don’t have it?” Smith asks.

Some of the students were international, adding an additional layer of complications. “I picked one and asked him to meet me on What’s App,” Smith says. She asked him if he knew someplace in the community that might work with Penn. The next day, Smith heard from him. He was calling from a store in Kigali, Rwanda, and Smith tried to give a credit card to the employee there. They wouldn’t take that form of payment. Smith asked if she could wire the funds and pulled in Varas. Because the store was such a small company, Penn couldn’t wire the money to a bank, Smith says. The only option was Western Union.

“Then I realized, wait a minute,” There were other students in the area,” Smith says. She asked the store owner if she could wire the funds for all the students and he could he get laptops to them. He agreed.

“So that was Friday,” Smith says. “I turned it over to Elaine, and they wired the money. I’m in bed, it’s like 1 a.m., and I hear my What’s App go off. So, I go and I look, and it’s the gentleman in Rwanda.” He had gone to get the Western Union funds and the police stopped him, saying they needed documentation from the institution on letterhead to verify the agreement. Smith got out of bed and got it done.

“It was definitely a piece that we, as an institution, had never embarked on before,” Varas says. “We were treading on brand new territory.”

Once they had a protocol in place, SIS and financial aid used this method to procure laptops for other international students, Smith says. “That’s one of my proudest moments.” Coming up with creative responses to support and advocate for students is “what we do in SIS,” says Smith. “We have a playbook like anyone else; we have protocols and so forth. But every single case that I’ve worked on, they have nuances that are just unique to what we do.”

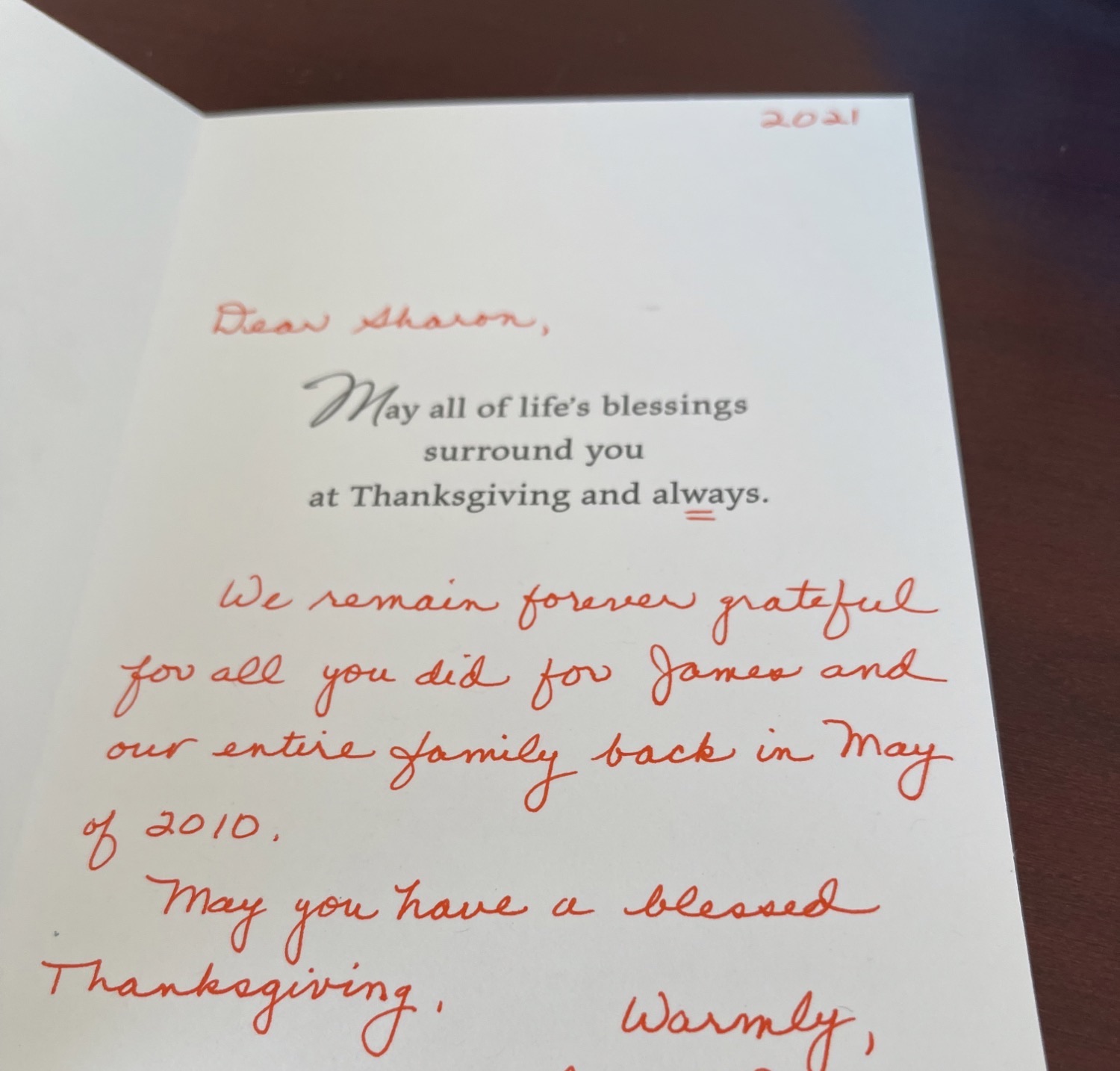

The most challenging aspect of the job is informing the family that a student is injured, missing, or deceased, Smith says. The instances where SIS is able to make a difference—to connect a student to counseling services or house a family whose child is in the hospital after a car collision—are extremely rewarding, Smith says. Some families send the office Christmas cards every year.

“We’re seeing many students at one of the hardest times of their lives,” Rudick says. Watching them graduate is “our proudest day, to know the obstacles that they overcame in order to get there and to see their pride and their happiness in being able to achieve their goals.”