Our Alums in Their Spaces: Krista Cortes | Director, La Casa Latina

Krista Cortes’ book-filled office on the top floor of the ARCH Building on Locust Walk is quiet, cozy, and full of golden, autumnal light. But the director of Penn’s La Casa Latina—the campus hub for Penn’s Latine community and Latin American culture—is more often found posted up in La Casa’s bright, bustling home on the garden level, chatting with students, organizing programming, and welcoming people into the space.

How a space is organized and outfitted for optimal learning and inclusion is important to her. After finishing her two master’s programs at Penn GSE (in teacher education and language and literacy), Cortes earned her PhD in education at the University of California, Berkeley, where her dissertation explored how Afro-Puerto Rican mothers create learning environments for their children that center Blackness.

“That’s what I’m trying to do in my work here,” said Cortes, who is also teaching “Applied Linguistics in Education” at GSE this semester. “It’s really important to me to bring Afro-Latinidad into conversations in a Latine cultural center. . . . I want us to really think about the multiplicity within our understanding of Latinidades. How do we do that, not only through programming, but how we do that in our interactions with students? How we do that in the ways that our space is designed?”

That care and intentionality is obvious throughout her office and at La Casa. She gave us a tour of everything from the personally meaningful art she’s hung on her walls to the snack closet she keeps stocked with condiments—Valentina hot sauce, Tajin chili-lime seasoning, adobo seasoning—to remind students of a taste of home.

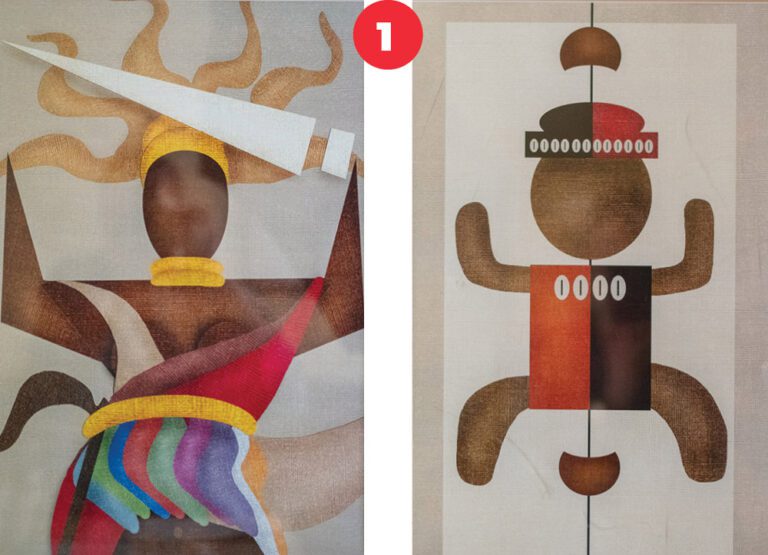

1. Orisha prints

I practice Santería—that’s my religion. Santería is an Afro-Cuban religion that came to Cuba when enslaved people from Africa who practiced Yoruba were brought over. These are representations of orishas [spirits] that are really important to me. That’s Oya—goddess of the wind, who represents transformation—with the sword, and Oshun—the river deity [not pictured], who represents love—is behind my desk. And there’s Elegua—deity of the crossroads, who represents destiny. I think they are super important as a lens or a metaphor through which to understand the ways in which Afro-Latinidad is often obscured and not talked about. . . . Even in thinking about the way that this tradition has persisted over time, it very much had to be hidden, right? To keep their traditions alive, they had to hide them behind Catholicism, and then Santería is really a blending of the Yoruba traditions with Catholicism as a way to adapt to a new situation. When folks come in my office, I don’t know that they would know what these images are. But it was important—a way of me bringing a piece of myself into this space.

2. Prints of Puerto Rico

I inherited these when my grandfather passed away and my grandmother asked me to help clean his room. In the back of his closet, I found this canister of prints like ones my grandmother has hanging in her home. . . . They are of streetscapes in Puerto Rico, which is where my grandparents and parents were born. I grew up on Long Island. But for me, the identity that is important to me is my “Puerto Ricanness.” That’s how I understand myself. These prints are like me trying to bring the idea of “a home that is not here” into this space.

3. Spiderman and La Borinqueña comic books

These feature Miles Morales, the Afro-Puerto Rican Spiderman, and La Borinqueña, who is also Afro-Puerto Rican. She’s a superhero that is meant to save Puerto Rico, so she talks about eco-feminism and climate justice. There was a comic shop in Berkeley that I was able to get some of these from. While I was in California, I met the author of the La Borinqueña comic books, Edgardo Miranda-Rodriguez, and he signed some of them for me. Folks really are into superheroes, and these have become a conversation-starter with students.

4. Día de los Muertos decorations

These are the boxes we’ve been packing for Día de los Muertos. They are full of supplies that we use to build an altar. We began this partnership with the College Houses—we give them all the supplies, and then usually a resident advisor or graduate resident advisor will make a program out of it where they build the altar in a common area in their College House. . . . Día de los Muertos is very much associated with Mexicanness. But it’s actually a practice that is celebrated all over Latin America and the Caribbean and beyond. It’s a cross-cultural practice. Lots of cultures honor their dead and want to remember their passed loved ones.

Director of La Casa Latina, Krista Cortes centers Blackness and celebrates the multiplicity inherent in ‘Latinidades.’

Walking into Krista L. Cortes’ home, visitors might be hit by the smell of sofrito, that cornerstone of Caribbean cooking, and see her children helping in the kitchen. “Sofrito is like a labor of love; it takes a lot of time,” Cortes says. “And since my oldest son was about 2 years old, he’s always helped me.” The food she makes for her family—plantains, rice and beans—helps connect them to their culture. For Puerto Rican Cortes and her Cuban husband, rooting their children in Afro-Latinx identity also means having bilingual and Spanish-language books, watching movies with Black protagonists, and having pictures of family, “which runs the gamut in color,” Cortes says, as well as artwork featuring orishas hung on the walls. Cortes and her husband practice Santería and the orishas are important intermediaries between humanity and divinity. “You walk into my house and the first thing you see are guerreros [warriors]: Eleggúa, Oggún, or Ochosi. That, to me, is an artifact of our Blackness.”

Cortes, who earned two master’s degrees from Penn’s Graduate School of Education and a Ph.D. in education from the University of California, Berkeley, is bringing this sense of Blackness home to La Casa Latina, one of six cultural resource centers at Penn. Cortes uses the term “Latinidades,” instead of the traditional “Latinidad,” to refer to the plurality inherent in all the different people, cultures, races, and languages that comprise Latin heritage. It’s not just one thing, she says, and in America that often gets lost in translation.

“There’s a white-washing of Latinidad that happens in popular media. One of the opportunities to counter this is within the university setting. For the 10th annual Dolores de la Huerta lecture, Cortes invited two Haitian women, Maika and Maritza Moulite, to present. That was intentional. We love to talk about Latin America and the Caribbean and think about the Caribbean in its entirety when it suits us, but non-Spanish-speaking countries often get left out. People forget that Haiti and the Dominican Republic are actually one island; two countries share that space.Inviting Haitian speakers was a way that I’m trying to show folks that this is an issue that’s important to the Latinx community.”

Krista L. Cortes: New Director for The Center for Hispanic Excellence: La Casa Latina

Penn alumna Krista L. Cortes has been appointed director of La Casa Latina, the main hub for Latinx students, with the goal to make space for Afro-Latinx students within the greater Latinx community.

Since her appointment in late January, Cortes said her chief objectives as director are to implement programming that connects Penn’s Latinx community with the greater Philadelphia Latinx community, and also to turn the cultural center into a Black-affirming space so Afro-Latinx students feel welcomed as well.