Greenfield Intercultural Center celebrates 40 year anniversary, reflects on history at Penn

The Greenfield Intercultural Center commemorated its 40th anniversary on Jan. 27.

GIC was established in 1984 to support the University’s underrepresented communities and build intercultural awareness on campus. As Penn’s first intercultural center, the GIC has provided a space for numerous student affinity groups over the years – including the United Minorities Council, Natives at Penn, and the Alliance for Understanding.

The center was founded in response to a UMC petition calling for the creation of a campus center for underrepresented students. Since its inception, GIC has supported many different initiatives, programs, and communities. It was a key advocate that pushed for the University to create community hubs, such as Makuu, La Casa Latina, and PAACH.

“GIC has set a vital model for how universities can better support their students and educate society on intercultural belonging,” GIC Associate Director Kia Lor said.

Lor added that the center has served as an “intercultural incubator of new ideas and programs” over the past four decades.

Around 2015, the GIC aided in the establishment of Penn First Plus, which has since become a community to bolster the successes of first generation and low income students.

GIC Director Valeria De Cruz spoke to the center’s platform as a guiding force for new community groups on campus. She said that the GIC team was thankful for the opportunity to mentor and be a point of consultation for students that aim to develop their passions and leadership skills.

“As one of the oldest centers at Penn, the GIC is often sought out for expertise and guidance from newer departments and centers on best practices in building and supporting diverse communities,” De Cruz said.

De Cruz reflected on the University’s relationship with the center, acknowledging the financial and directional support they’ve received.

“Since the GIC was established, [it has] received consistent budgetary support from the university and University Life has been instrumental in providing guidance as the center has worked to address the needs of different communities,” she said.

To celebrate its 40th anniversary, GIC recognized local alumni who are making change in the community at an Open House Celebration on Jan. 27. In the fall, the center plans on hosting a gala to bring together alumni located nationally and globally.

De Cruz highlighted the importance of the alumni network in continuing GIC’s work. “The center benefits from generous alumni support which has enabled us to increase our visibility and extend our reach on campus, ” De Cruz said.

New Leadership Announced at the LGBT Center

Eric Anglero (they/them) was appointed as the new Director of University of Pennsylvania’s LGBT Center, Associate Vice Provost for University Life Will Atkins announced. Following an extensive national search, Anglero brings a wealth of knowledge, experience, and aspirations to the role.

Anglero joins Penn from Princeton University’s Gender and Sexuality Resource Center, where they provided training for community partners, supervised staff, and helped oversee its direction and mission. In addition to their role at Princeton, Anglero currently serves on an alumni board at Stockton University and the executive board at COLAGE, an organization for people with one or more queer parents and/or caregivers.

“I am elated to join the historic tradition at Penn and the incredible staff of the LGBT Center,” said Anglero. “I look forward to being a contributor to the work of the broader Cultural Resource Centers in University Life and look forward to meeting with the campus community.”

Anglero earned their Master of Arts in American Studies at Stockton University.

Additionally, Wesley (Wes) Alvers (they/them) will serve as the newly appointed Associate Director. They hold a Master of Social Work degree from Penn, specializing in macro practice for LGBTQ+ populations. Alvers previously served as the LGBT Center’s Program Coordinator, and they are committed to supporting and advocating for queer and trans communities at Penn.

Both Anglero and Alvers began their current roles on January 8. Continued gratitude is extended to Jake Muscato, Loren Grishow-Schade, and all LGBT Center staff who worked collaboratively to ensure seamless support for students throughout this transition. Malik Muhammad, who helped lead search efforts for the positions, will continue his work at Penn as the Director for Social Justice and Inclusion Initiatives in University Life.

University Life and the LGBT Center look forward to an exciting semester ahead with both new and existing staff at the helm.

Our Alums in Their Spaces: Krista Cortes | Director, La Casa Latina

Krista Cortes’ book-filled office on the top floor of the ARCH Building on Locust Walk is quiet, cozy, and full of golden, autumnal light. But the director of Penn’s La Casa Latina—the campus hub for Penn’s Latine community and Latin American culture—is more often found posted up in La Casa’s bright, bustling home on the garden level, chatting with students, organizing programming, and welcoming people into the space.

How a space is organized and outfitted for optimal learning and inclusion is important to her. After finishing her two master’s programs at Penn GSE (in teacher education and language and literacy), Cortes earned her PhD in education at the University of California, Berkeley, where her dissertation explored how Afro-Puerto Rican mothers create learning environments for their children that center Blackness.

“That’s what I’m trying to do in my work here,” said Cortes, who is also teaching “Applied Linguistics in Education” at GSE this semester. “It’s really important to me to bring Afro-Latinidad into conversations in a Latine cultural center. . . . I want us to really think about the multiplicity within our understanding of Latinidades. How do we do that, not only through programming, but how we do that in our interactions with students? How we do that in the ways that our space is designed?”

That care and intentionality is obvious throughout her office and at La Casa. She gave us a tour of everything from the personally meaningful art she’s hung on her walls to the snack closet she keeps stocked with condiments—Valentina hot sauce, Tajin chili-lime seasoning, adobo seasoning—to remind students of a taste of home.

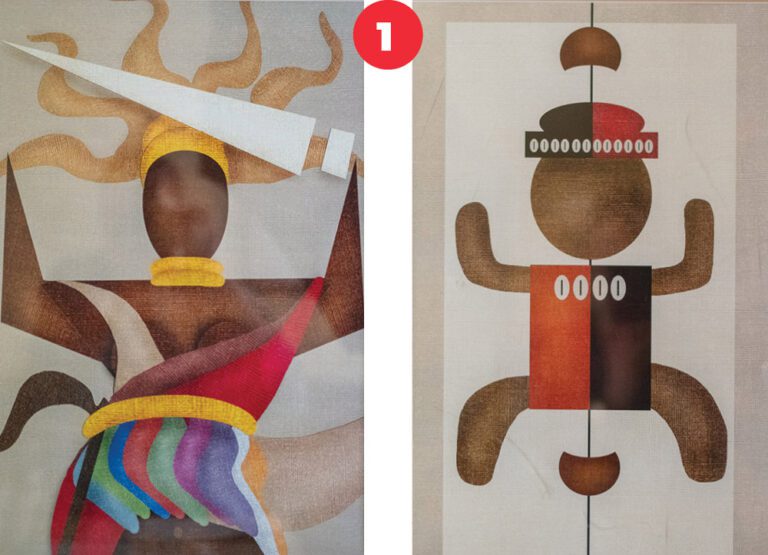

1. Orisha prints

I practice Santería—that’s my religion. Santería is an Afro-Cuban religion that came to Cuba when enslaved people from Africa who practiced Yoruba were brought over. These are representations of orishas [spirits] that are really important to me. That’s Oya—goddess of the wind, who represents transformation—with the sword, and Oshun—the river deity [not pictured], who represents love—is behind my desk. And there’s Elegua—deity of the crossroads, who represents destiny. I think they are super important as a lens or a metaphor through which to understand the ways in which Afro-Latinidad is often obscured and not talked about. . . . Even in thinking about the way that this tradition has persisted over time, it very much had to be hidden, right? To keep their traditions alive, they had to hide them behind Catholicism, and then Santería is really a blending of the Yoruba traditions with Catholicism as a way to adapt to a new situation. When folks come in my office, I don’t know that they would know what these images are. But it was important—a way of me bringing a piece of myself into this space.

2. Prints of Puerto Rico

I inherited these when my grandfather passed away and my grandmother asked me to help clean his room. In the back of his closet, I found this canister of prints like ones my grandmother has hanging in her home. . . . They are of streetscapes in Puerto Rico, which is where my grandparents and parents were born. I grew up on Long Island. But for me, the identity that is important to me is my “Puerto Ricanness.” That’s how I understand myself. These prints are like me trying to bring the idea of “a home that is not here” into this space.

3. Spiderman and La Borinqueña comic books

These feature Miles Morales, the Afro-Puerto Rican Spiderman, and La Borinqueña, who is also Afro-Puerto Rican. She’s a superhero that is meant to save Puerto Rico, so she talks about eco-feminism and climate justice. There was a comic shop in Berkeley that I was able to get some of these from. While I was in California, I met the author of the La Borinqueña comic books, Edgardo Miranda-Rodriguez, and he signed some of them for me. Folks really are into superheroes, and these have become a conversation-starter with students.

4. Día de los Muertos decorations

These are the boxes we’ve been packing for Día de los Muertos. They are full of supplies that we use to build an altar. We began this partnership with the College Houses—we give them all the supplies, and then usually a resident advisor or graduate resident advisor will make a program out of it where they build the altar in a common area in their College House. . . . Día de los Muertos is very much associated with Mexicanness. But it’s actually a practice that is celebrated all over Latin America and the Caribbean and beyond. It’s a cross-cultural practice. Lots of cultures honor their dead and want to remember their passed loved ones.

Kwanzaa at Penn

Kwanzaa, a cultural holiday celebrating the cultures of Africa and the African diaspora, is celebrated from Dec. 26 through Jan. 1. At Penn, a celebration was held in the ARCH building with a ceremony and feast, offering sustenance and support for students during the final stretch of their fall semester.

“What we hope this moment does for you is just energize, recharge,” said Brian Peterson, director of Makuu: The Black Cultural Center, urging students to “summon that sense of purpose” during finals.

Peterson advised students to stay focused and offered help. He said, “Life is challenging. If you’re having problems staying focused, come to this building. It’s quiet. Knock on my door. Let me know what you have to do,” Peterson said. “And I might ask you to check in on me.”

Charles “Chaz” Howard, University chaplain and vice president for social equity & community, gave a word of prayer and offered libations, a Kwanzaa tradition honoring forebearers. Members of the audience offered names of people who have died: James Baldwin, Audre Lorde, and Sadie T. M. Alexander among them. After each name, Howard poured out a measure of water, offering acknowledgement and thanks.

Student leaders from UMOJA then reviewed the seven principles of Kwanzaa: Umoja, or unity; Kujichagulia, or self-determination, Ujamaa, or cooperative economics; Ujima, or collective work and responsibility; Noa, or purpose, Kuumba, or creativity; and Imani, or faith.

At the event’s close, Peterson urged students to offer support and to take care of one another. “Let’s remember we do control that,” he said. “It sounds cliché, but we do change the world.”

Penn student, finalist for Oticon Focus on People Awards, advocates for those with hearing loss

Yaduraj Choudhary (C’27 W’27) is confronting his hearing loss through advocacy work and his student-led non-profit organization, Three Tiny Bones. The organization is dedicated to creating a more inclusive society by educating communities about healthy hearing and destigmatizing hearing loss. Choudhary was recently featured on Fox29, promoting his efforts and recognition as a finalist for the Oticon Focus on People Awards. These awards honor individuals with hearing loss who actively contribute to spreading awareness, education, and support within their communities.

New Faces, Same Mission: 50 Years of the Penn Women’s Center

Content warning: The following article includes mentions of rape, sexual violence, and murder, and can be disturbing and/or triggering for some readers. Please find resources listed at the bottom of the article.

In the early ‘70s, news of sexual assault on campus traveled in the forms of rumors and whispers.

“No one could confirm what was really happening,” Carol Tracy (C ‘76) says. “Because of the rumor mill, we didn’t know if there was one [assault] in Houston Hall or five.”

Before 1973, no woman on Penn’s campus was thinking about safety, or at least no woman that Tracy knew. But when the stories of sexual assault around campus began circulating, this changed.

From Tracy’s perspective, the rumors were largely ignored by Penn’s administration, contributing to a climate of fear for women on campus. When two nursing students were gang–raped in the SEPTA station at 34th and Chestnut streets in March of 1973, a group of Penn students decided they could no longer ignore the problem.

Tracy had been previously involved in feminist activism at Penn. She came to Penn as a secretary in 1968, taking night classes until she was able to enroll as a full–time student. Throughout that time, she was focused on a union movement for secretaries. But in 1973, her activism focus shifted to sexual harassment.

In April of that year, students and community members organized a sit–in at College Hall that would eventually lead to the founding of the Penn Women’s Center. The PWC still exists, offering a community space for gender equity on Penn’s campus, Director Elisa Foster says. Fifty years after the sit–in, their mission remains the same, even if the faces who are leading it have changed.

1973 was the height of the second–wave feminist movement, when equality for women was at the forefront of social activism. The Equal Pay Act was passed in the previous decade, prohibiting sex–based discrimination. Title IX had been enacted the year before, ending Penn’s gender–segregated honor societies. In January of that year, the United States Supreme Court ruled on Roe v. Wade, protecting abortion rights.

“With Title IX, people weren’t even thinking about sexual harassment,” Tracy says. While the Equal Pay Act, Title IX, and Roe v. Wade were legal victories, “sexual assault and domestic violence was the one issue that didn’t come from legislators but from grassroots movements.”

This grassroots organizing approach is what fueled the sit–in at College Hall. Efforts to start a Women’s Studies program at Penn were well underway, and students began to consider the best way to handle the assault rumors on campus. Survivors weren’t the ones to come forward; rather, it was students worried about it happening to them.

The students had previously met with the director of public safety to learn more about what was going on and how to stay safe. In the meeting, he offered them advice: Don’t wear provocative clothing.

“My response was, ‘I should be able to walk down Locust Walk buck naked and it’s still your job to protect me,” Rose Weber (C ‘75, L ‘96) says. “That meeting was the real catalyst that just got us mad enough that we decided we needed to sit–in.”

A few days after the meeting, Robin Morgan, radical feminist and author of Sisterhood is Powerful, came to give a campus talk by invitation from the English department. “She said, ‘You absolutely have to do something. This can’t go on,” Tracy recalls.

So students gathered in the Christian Association basement to make a plan. “Any story about the development of the Women’s Center has to take the CA into account,” former CA intern Betsy Sandel says. Later renamed Concern through Action, the anti–war movement had just ended, and the CA had been “the place for everything” throughout the protests. The students returned there to plan.

Their decision: a sit–in, one of the first all–women sit–ins on a college campus, and among the most influential.

“This was truly a collective moment,” Tracy says. “Students and community members worked really closely together to create a safe space for women on campus.”

Former Psychiatry and History professor Caroll Smith–Rosenberg and Tracy were the key negotiators, sitting around a table in College Hall with the president, provost, dean of students, and several other administrators.

They presented the group’s list of demands, which included better lighting on campus, a bus service, alarms in bathrooms, staffing of a senior–level policewoman to support assault survivors, the right to bring their dogs to class, and of course, the Women’s Center.

As they negotiated, over 200 students and community members occupied College Hall. “We just congregated. It was a huge number of people,” Sandel says. “And it wasn’t just all women. There were lots of male faculty and male students too, but mostly women, just congregated in the hallways.”

The group was careful not to violate open expression guidelines. They lined the hallways, ensuring they didn’t prevent anyone from entering the building or getting to their classes. Local restaurants provided food, and they slept in sleeping bags on the floor for four days.

As Tracy and Smith–Rosenberg continued negotiations, the dean of students received a note requesting their permission to rent College Hall 200, which had been the protest hotspot of the anti–war movement. He was surprised, telling Tracy that protests usually don’t rent the room. “Well, I’m sorry,” Tracy recalls Smith–Rosenberg responding. “Women are overly socialized, and we’re just going to stay until this is over.”

When Friday rolled around, the College Hall security guards were under the impression that the protestors would pack up and go home for the weekend. “By late afternoon, they realized we were really and truly going to stay as long as it took, and they basically caved,” Weber says.

Negotiations were straightforward. Every demand was met, much to the organizers’ surprise. In fact, Weber never expected the Women’s Center to become a reality—it was a throwaway demand, designed to be something they were willing to give up during negotiations.

“It was pretty clear the University had to do something,” Sandel says. “There was serious fear and danger, plus a public relations crisis.”

Getting the center off the ground was a “process,” according to Weber, but a process that moved quickly. Housed in Logan Hall (since renamed Claudia Cohen Hall), the PWC became a place for women to connect with each other and engage in activist work.

They also developed educational opportunities, including the Free Women’s School, a ‘courses without credit’ program offering women from Penn and the greater Philadelphia area an education in “areas not usually offered in the college curriculum,” Sandel says.

Filipino language and culture

Eight thousand miles away from Philadelphia lies the Philippines, a tropical archipelago dotting the Pacific Ocean. Its 117 million inhabitants speak more than 120 languages, including the country’s national language, Filipino, a modernized version of the indigenous Tagalog with loan words from English, Spanish, and Chinese.

It’s also one of the most spoken languages in the United States. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Filipino is the fourth most spoken language following English, Spanish, and Chinese, but Filipino language classes are rare, even at the college level. At Penn, they’ve been offered since 1996.

This semester, Vicky Faye Aquino, is teaching Beginning Filipino to 13 students every Tuesday and Thursday evening, with the assistance of Deo Mar Suasin, a teaching assistant and Fulbright Visiting Scholar from the Philippines who is also taking classes in the Graduate School of Education. Many of the students enrolled in the course so they can connect with their heritage and communicate with their families, Aquino says.

Though raised bilingual, Katrina Verano, a second-year student majoring in mathematics from Malvern, Pennsylvania, says she stopped practicing Tagalog during elementary school because there was no one else her age to converse with. “I was the only Filipino in my high school. I really took it to heart,” she says. “It was always only me.”

Verano says she regrets that she no longer remembers the language and is taking the class to rectify that. “I want my kids to be able to speak Tagalog. I was so grateful that my parents taught me,” she says. “I felt like it was really a gift. In order for me to stay connected as strong as I want to be, I have to speak the language.”

Many first-born Filipino Americans were not taught to speak their parents’ language, Verano says, including her cousins and most students in the class. Some students say their parents didn’t teach Filipino to them fearing they would pick up an accent or not excel at school. Assimilating and fitting in was the goal.

Jonathan Villegas, a third-year mechanical engineering major from Pasadena, California, is biracial, and his Filipino father came to the U.S. for college at age 18. Villegas says his father “doesn’t talk about it much. He had some negative experiences being Filipino in L.A.” and felt he was passed up for jobs and promotions.

Villegas heard about the class from another friend who had previously enrolled. Before that, learning Filipino “honestly never really occurred to me,” Villegas says. “I assumed it wouldn’t be available. A lot of colleges don’t have it.”

At Penn, the program was started by Erlinda Juliano 27 years ago. As she was preparing for her retirement, Juliano met Aquino at a Filipino cultural event called Barrio, hosted by the Penn Philippine Association, and started asking pointed questions. Was Aquino originally from the Philippines? She was. Does she speak Filipino fluently? She does. Had she ever taught the language before? She had.

Juliano encouraged Aquino to apply for the lecturer position. Aquino almost hesitated. She already had a full-time job as the associate director at the Pan-Asian American Community House (PAACH) and a 2-year-old daughter at home.

But the language is important to her, Aquino says. She didn’t want students to miss the chance of learning how to speak their heritage language.

Aquino stays late twice a week to teach her students, bringing movies, art, culture, and music into the classroom. Aquino took students to the Penn Museum to look at artifacts from the Philippines. She brings in cultural components, teaching the students slang and showing contemporary videos. On Oct. 31, the students are headed to PAACH for “Halo-Halloween.” Halo-Halo is an elaborately layered, special occasion dessert. There will also be singing because “Karaoke is part of our culture,” she says. “It’s not just a language class.”

Polyglot Oksana De Mesa, a clinical research nurse at the Perelman School of Medicine, is originally from Ukraine. She grew up speaking Ukrainian, learned Russian when her family immigrated to Chicago, added Mandarin, and dabbled in Spanish, Japanese, and Korean. De Mesa loves languages and enrolled in the course so she could speak with her husband in his native tongue, she says. “Plus, it would be nice to impress my in-laws eventually, especially Lola Luz, the grandmother.” (Lola means grandmother in Filipino.)

De Mesa’s Spanish has come in handy because of the abundance of Spanish loan words in Filipino, she says. This includes common vocabulary like sala (living room), gwapo (handsome; guapo in Spanish) and mundo (world), recognized in Filipino along with the Tagalog word for world, daigdig.

The commonalities are no coincidence. Spain colonized the Philippines for more than 300 years until 1898, when it ceded the region to the U.S. at the end of the Spanish-American War. The U.S. established military rule over the country and remained in power until Japanese occupation during World War II. The Philippines gained independence in 1945.

Now, Aquino says, Filipinos have a great sense of national pride in their language and culture, and students living in the diaspora want to take part. In one class, at Aquino’s urging, Verano led the class in singing the anthem, “Lupang Hinirang,” which means “Chosen Land.”

Aquino, who grew up in the Philippines, says, “Every morning, we had to sing the national anthem, place our hands over our hearts.” Most of her students had heard the anthem before. “Honestly, it’s kind of a banger,” says one of the students, and her classmates laugh and nod.

Hearing the students learn and speak Filipino is the most gratifying part of the work, Aquino says. Even though she is away from her daughter, “it’s for her, too,” Aquino says, and an important part of perpetuating the language and cultural knowledge.

Sefora Elish, a first-year nursing student from Syosset, New York, calls her grandparents to share what she’s learned after every class. They taught her a few words, she says, but mainly switched to Filipino when they wanted to tell secrets, she says. When Elish saw the language offered at Penn, “I had to do it,” she says. “It’s important because a lot of schools don’t offer it.” Often in class, Elish finds herself saying, “Oh, I know that word, but now I can put it in a sentence.”

As for Villegas, he hasn’t yet told his family in California that he’s learning Filipino. He’s going to wait. Then, during Winter Break, he can greet and surprise his grandparents with “Mano po. Kumusta po kayo,” a traditional way of greeting elders. “It’s going to be a Christmas present,” he says.

(While the terms “Filipino” and “Tagalog” refer to different variations of the language, they are used interchangeably by speakers in this story.)

“A Place I Could Be Myself”

The Penn Women’s Center celebrates five decades of providing advocacy, advising, refuge, counseling, company, and tea. From its origins in the struggle against campus sexual violence, the center has evolved to tackle a range of concerns, from wellness to combating racism. The latest debate: Is its name, meant to be welcoming, too restrictive or exclusionary at a time when gender itself is contested?

On a mild late-summer afternoon, soon after the semester’s start, a purple-and-white banner announcing an open house is attracting both the avid and the merely curious.

“I’m a woman. I like to be in spaces where other women support each other, and that’s obvious when you see the words ‘Women’s Center,’” says Leigh Monistere GrEd’28, a first-year student at the Graduate School of Education. The founder of a literacy nonprofit, she is among a stream of students investigating the Penn Women’s Center, housed in the former Theta Xi fraternity house at the corner of Locust Walk and 37th Street.

On the porch, visitors snag free T-shirts celebrating the center’s 50th anniversary and proclaiming, “Growth. Action. Solidarity.” Inside, they crowd around a table to iron decorative decals onto pouches with the center’s logo.

There’s free food, too: chocolate-covered pretzels in the living room, cheese and fruit in the eco-kitchen, with its energy-efficient appliances, cork floors, and cabinets of reclaimed wood. In the backyard garden students chat with Women’s Center staff over lavender lemonade and iced English breakfast tea. On the patio are chiseled quotes by women writers and other icons of feminism and civil rights. From Alice Walker, author of The Color Purple, comes this gentle observation: “In search of my mother’s garden, I found my own.”

Since 1973, the year of its founding, the Penn Women’s Center—which relocated in 1996from Houston Hall—has been a refuge, gathering place, and resource center for the Penn community, including faculty and staff: women mostly, but also sexual minorities and the gender nonconforming, and sometimes their straight male allies.

“The Penn Women’s Center was also a home for young gay or LGBT students,” says Daren Wade C’88 SW’94, now associate director of career development at the University of Washington’s School of Public Health. “It was very much a place that I felt like I could be myself.”

Mika Rao C’96, who was president of the South Asia Society at Penn, says she relied on the Women’s Center to help a friend with financial problems stay in school. When members of the South Asia Society faced an incident of racial intimidation, “the first thought I had was, ‘Let’s call the Penn Women’s Center,’” says Rao, now managing director of williamsworks, a philanthropy consulting firm. “What I found was that the Women’s Center was just there to support women, period, and [help them] navigate a very large, complex university system.”

Born out of concerns about sexual violence, the center also has provided a locale for a meeting or hangout, a cup of tea, career advice, quiet study, or confidential counseling. Programming over the years has tackled the nuts-and-bolts feminist issues of sexual harassment, pay equity, and reproductive rights, but also wellness and carpentry skills. The center has been at the nexus of University-wide struggles to better the status of both women and minorities, helping to spawn a range of affinity and activist groups. It was intersectional and anti-racist long before the terms became buzzwords.

But much of its agenda wasn’t explicitly political. In recent years, new mothers—including the center’s current director, Elisa C. Foster—could avail themselves of a lactation center. A small crafts room provides yarn, fabric, and a sewing machine. Along with feminist classics, the library offers poetry by Anne Sexton, Jeffrey Eugenides’ novel Middlesex, and the stories of Gertrude Stein. A 2017 volume titled Crafting the Resistance: 35 Projects for Craftivists, Protestors, and Women Who Persist has helped inspire center programming, Foster says.

The Women’s Center’s conference room is temporarily overflowing with stacks of newspaper articles and other documents. In honor of the anniversary, Foster is assembling an archival display that will debut during Homecoming Weekend. Spring semester events will include a joint symposium with the Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies Program [see sidebar] and a May 18 celebration during Alumni Weekend.

The yearlong anniversary also will be an occasion for the Women’s Center to reevaluate its mission—and its name. “Nationally, at universities across the country, their Women’s Centers are changing their names to Gender Equity Centers,” says Foster. “We hear it from the students, we hear from the community that we serve, we hear it from the national trends.” A name change isn’t happening this year, but “it’s not off the table,” Foster says.