Greenfield Intercultural Center celebrates 40 year anniversary, reflects on history at Penn

The Greenfield Intercultural Center commemorated its 40th anniversary on Jan. 27.

GIC was established in 1984 to support the University’s underrepresented communities and build intercultural awareness on campus. As Penn’s first intercultural center, the GIC has provided a space for numerous student affinity groups over the years – including the United Minorities Council, Natives at Penn, and the Alliance for Understanding.

The center was founded in response to a UMC petition calling for the creation of a campus center for underrepresented students. Since its inception, GIC has supported many different initiatives, programs, and communities. It was a key advocate that pushed for the University to create community hubs, such as Makuu, La Casa Latina, and PAACH.

“GIC has set a vital model for how universities can better support their students and educate society on intercultural belonging,” GIC Associate Director Kia Lor said.

Lor added that the center has served as an “intercultural incubator of new ideas and programs” over the past four decades.

Around 2015, the GIC aided in the establishment of Penn First Plus, which has since become a community to bolster the successes of first generation and low income students.

GIC Director Valeria De Cruz spoke to the center’s platform as a guiding force for new community groups on campus. She said that the GIC team was thankful for the opportunity to mentor and be a point of consultation for students that aim to develop their passions and leadership skills.

“As one of the oldest centers at Penn, the GIC is often sought out for expertise and guidance from newer departments and centers on best practices in building and supporting diverse communities,” De Cruz said.

De Cruz reflected on the University’s relationship with the center, acknowledging the financial and directional support they’ve received.

“Since the GIC was established, [it has] received consistent budgetary support from the university and University Life has been instrumental in providing guidance as the center has worked to address the needs of different communities,” she said.

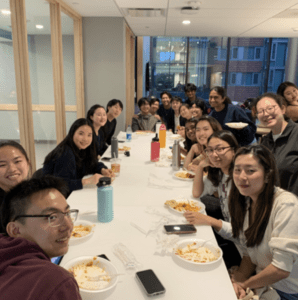

To celebrate its 40th anniversary, GIC recognized local alumni who are making change in the community at an Open House Celebration on Jan. 27. In the fall, the center plans on hosting a gala to bring together alumni located nationally and globally.

De Cruz highlighted the importance of the alumni network in continuing GIC’s work. “The center benefits from generous alumni support which has enabled us to increase our visibility and extend our reach on campus, ” De Cruz said.

New Leadership Announced at the LGBT Center

Eric Anglero (they/them) was appointed as the new Director of University of Pennsylvania’s LGBT Center, Associate Vice Provost for University Life Will Atkins announced. Following an extensive national search, Anglero brings a wealth of knowledge, experience, and aspirations to the role.

Anglero joins Penn from Princeton University’s Gender and Sexuality Resource Center, where they provided training for community partners, supervised staff, and helped oversee its direction and mission. In addition to their role at Princeton, Anglero currently serves on an alumni board at Stockton University and the executive board at COLAGE, an organization for people with one or more queer parents and/or caregivers.

“I am elated to join the historic tradition at Penn and the incredible staff of the LGBT Center,” said Anglero. “I look forward to being a contributor to the work of the broader Cultural Resource Centers in University Life and look forward to meeting with the campus community.”

Anglero earned their Master of Arts in American Studies at Stockton University.

Additionally, Wesley (Wes) Alvers (they/them) will serve as the newly appointed Associate Director. They hold a Master of Social Work degree from Penn, specializing in macro practice for LGBTQ+ populations. Alvers previously served as the LGBT Center’s Program Coordinator, and they are committed to supporting and advocating for queer and trans communities at Penn.

Both Anglero and Alvers began their current roles on January 8. Continued gratitude is extended to Jake Muscato, Loren Grishow-Schade, and all LGBT Center staff who worked collaboratively to ensure seamless support for students throughout this transition. Malik Muhammad, who helped lead search efforts for the positions, will continue his work at Penn as the Director for Social Justice and Inclusion Initiatives in University Life.

University Life and the LGBT Center look forward to an exciting semester ahead with both new and existing staff at the helm.

Our Alums in Their Spaces: Krista Cortes | Director, La Casa Latina

Krista Cortes’ book-filled office on the top floor of the ARCH Building on Locust Walk is quiet, cozy, and full of golden, autumnal light. But the director of Penn’s La Casa Latina—the campus hub for Penn’s Latine community and Latin American culture—is more often found posted up in La Casa’s bright, bustling home on the garden level, chatting with students, organizing programming, and welcoming people into the space.

How a space is organized and outfitted for optimal learning and inclusion is important to her. After finishing her two master’s programs at Penn GSE (in teacher education and language and literacy), Cortes earned her PhD in education at the University of California, Berkeley, where her dissertation explored how Afro-Puerto Rican mothers create learning environments for their children that center Blackness.

“That’s what I’m trying to do in my work here,” said Cortes, who is also teaching “Applied Linguistics in Education” at GSE this semester. “It’s really important to me to bring Afro-Latinidad into conversations in a Latine cultural center. . . . I want us to really think about the multiplicity within our understanding of Latinidades. How do we do that, not only through programming, but how we do that in our interactions with students? How we do that in the ways that our space is designed?”

That care and intentionality is obvious throughout her office and at La Casa. She gave us a tour of everything from the personally meaningful art she’s hung on her walls to the snack closet she keeps stocked with condiments—Valentina hot sauce, Tajin chili-lime seasoning, adobo seasoning—to remind students of a taste of home.

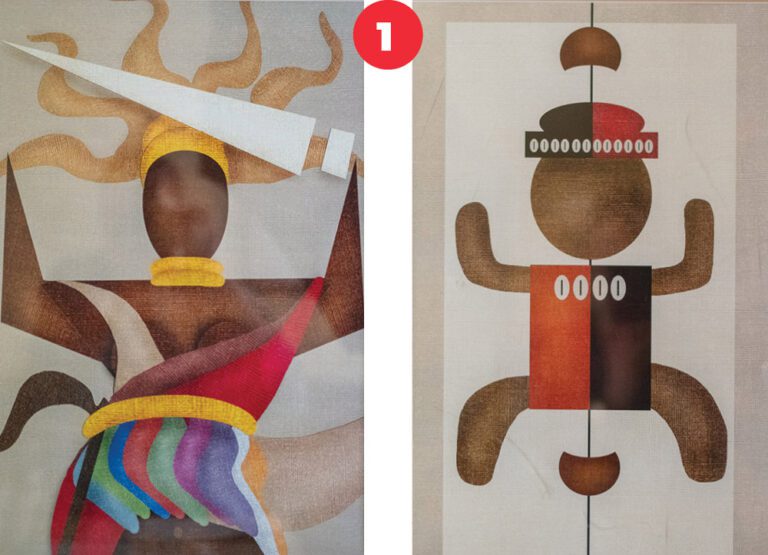

1. Orisha prints

I practice Santería—that’s my religion. Santería is an Afro-Cuban religion that came to Cuba when enslaved people from Africa who practiced Yoruba were brought over. These are representations of orishas [spirits] that are really important to me. That’s Oya—goddess of the wind, who represents transformation—with the sword, and Oshun—the river deity [not pictured], who represents love—is behind my desk. And there’s Elegua—deity of the crossroads, who represents destiny. I think they are super important as a lens or a metaphor through which to understand the ways in which Afro-Latinidad is often obscured and not talked about. . . . Even in thinking about the way that this tradition has persisted over time, it very much had to be hidden, right? To keep their traditions alive, they had to hide them behind Catholicism, and then Santería is really a blending of the Yoruba traditions with Catholicism as a way to adapt to a new situation. When folks come in my office, I don’t know that they would know what these images are. But it was important—a way of me bringing a piece of myself into this space.

2. Prints of Puerto Rico

I inherited these when my grandfather passed away and my grandmother asked me to help clean his room. In the back of his closet, I found this canister of prints like ones my grandmother has hanging in her home. . . . They are of streetscapes in Puerto Rico, which is where my grandparents and parents were born. I grew up on Long Island. But for me, the identity that is important to me is my “Puerto Ricanness.” That’s how I understand myself. These prints are like me trying to bring the idea of “a home that is not here” into this space.

3. Spiderman and La Borinqueña comic books

These feature Miles Morales, the Afro-Puerto Rican Spiderman, and La Borinqueña, who is also Afro-Puerto Rican. She’s a superhero that is meant to save Puerto Rico, so she talks about eco-feminism and climate justice. There was a comic shop in Berkeley that I was able to get some of these from. While I was in California, I met the author of the La Borinqueña comic books, Edgardo Miranda-Rodriguez, and he signed some of them for me. Folks really are into superheroes, and these have become a conversation-starter with students.

4. Día de los Muertos decorations

These are the boxes we’ve been packing for Día de los Muertos. They are full of supplies that we use to build an altar. We began this partnership with the College Houses—we give them all the supplies, and then usually a resident advisor or graduate resident advisor will make a program out of it where they build the altar in a common area in their College House. . . . Día de los Muertos is very much associated with Mexicanness. But it’s actually a practice that is celebrated all over Latin America and the Caribbean and beyond. It’s a cross-cultural practice. Lots of cultures honor their dead and want to remember their passed loved ones.

Penn student, finalist for Oticon Focus on People Awards, advocates for those with hearing loss

Yaduraj Choudhary (C’27 W’27) is confronting his hearing loss through advocacy work and his student-led non-profit organization, Three Tiny Bones. The organization is dedicated to creating a more inclusive society by educating communities about healthy hearing and destigmatizing hearing loss. Choudhary was recently featured on Fox29, promoting his efforts and recognition as a finalist for the Oticon Focus on People Awards. These awards honor individuals with hearing loss who actively contribute to spreading awareness, education, and support within their communities.

New Faces, Same Mission: 50 Years of the Penn Women’s Center

Content warning: The following article includes mentions of rape, sexual violence, and murder, and can be disturbing and/or triggering for some readers. Please find resources listed at the bottom of the article.

In the early ‘70s, news of sexual assault on campus traveled in the forms of rumors and whispers.

“No one could confirm what was really happening,” Carol Tracy (C ‘76) says. “Because of the rumor mill, we didn’t know if there was one [assault] in Houston Hall or five.”

Before 1973, no woman on Penn’s campus was thinking about safety, or at least no woman that Tracy knew. But when the stories of sexual assault around campus began circulating, this changed.

From Tracy’s perspective, the rumors were largely ignored by Penn’s administration, contributing to a climate of fear for women on campus. When two nursing students were gang–raped in the SEPTA station at 34th and Chestnut streets in March of 1973, a group of Penn students decided they could no longer ignore the problem.

Tracy had been previously involved in feminist activism at Penn. She came to Penn as a secretary in 1968, taking night classes until she was able to enroll as a full–time student. Throughout that time, she was focused on a union movement for secretaries. But in 1973, her activism focus shifted to sexual harassment.

In April of that year, students and community members organized a sit–in at College Hall that would eventually lead to the founding of the Penn Women’s Center. The PWC still exists, offering a community space for gender equity on Penn’s campus, Director Elisa Foster says. Fifty years after the sit–in, their mission remains the same, even if the faces who are leading it have changed.

1973 was the height of the second–wave feminist movement, when equality for women was at the forefront of social activism. The Equal Pay Act was passed in the previous decade, prohibiting sex–based discrimination. Title IX had been enacted the year before, ending Penn’s gender–segregated honor societies. In January of that year, the United States Supreme Court ruled on Roe v. Wade, protecting abortion rights.

“With Title IX, people weren’t even thinking about sexual harassment,” Tracy says. While the Equal Pay Act, Title IX, and Roe v. Wade were legal victories, “sexual assault and domestic violence was the one issue that didn’t come from legislators but from grassroots movements.”

This grassroots organizing approach is what fueled the sit–in at College Hall. Efforts to start a Women’s Studies program at Penn were well underway, and students began to consider the best way to handle the assault rumors on campus. Survivors weren’t the ones to come forward; rather, it was students worried about it happening to them.

The students had previously met with the director of public safety to learn more about what was going on and how to stay safe. In the meeting, he offered them advice: Don’t wear provocative clothing.

“My response was, ‘I should be able to walk down Locust Walk buck naked and it’s still your job to protect me,” Rose Weber (C ‘75, L ‘96) says. “That meeting was the real catalyst that just got us mad enough that we decided we needed to sit–in.”

A few days after the meeting, Robin Morgan, radical feminist and author of Sisterhood is Powerful, came to give a campus talk by invitation from the English department. “She said, ‘You absolutely have to do something. This can’t go on,” Tracy recalls.

So students gathered in the Christian Association basement to make a plan. “Any story about the development of the Women’s Center has to take the CA into account,” former CA intern Betsy Sandel says. Later renamed Concern through Action, the anti–war movement had just ended, and the CA had been “the place for everything” throughout the protests. The students returned there to plan.

Their decision: a sit–in, one of the first all–women sit–ins on a college campus, and among the most influential.

“This was truly a collective moment,” Tracy says. “Students and community members worked really closely together to create a safe space for women on campus.”

Former Psychiatry and History professor Caroll Smith–Rosenberg and Tracy were the key negotiators, sitting around a table in College Hall with the president, provost, dean of students, and several other administrators.

They presented the group’s list of demands, which included better lighting on campus, a bus service, alarms in bathrooms, staffing of a senior–level policewoman to support assault survivors, the right to bring their dogs to class, and of course, the Women’s Center.

As they negotiated, over 200 students and community members occupied College Hall. “We just congregated. It was a huge number of people,” Sandel says. “And it wasn’t just all women. There were lots of male faculty and male students too, but mostly women, just congregated in the hallways.”

The group was careful not to violate open expression guidelines. They lined the hallways, ensuring they didn’t prevent anyone from entering the building or getting to their classes. Local restaurants provided food, and they slept in sleeping bags on the floor for four days.

As Tracy and Smith–Rosenberg continued negotiations, the dean of students received a note requesting their permission to rent College Hall 200, which had been the protest hotspot of the anti–war movement. He was surprised, telling Tracy that protests usually don’t rent the room. “Well, I’m sorry,” Tracy recalls Smith–Rosenberg responding. “Women are overly socialized, and we’re just going to stay until this is over.”

When Friday rolled around, the College Hall security guards were under the impression that the protestors would pack up and go home for the weekend. “By late afternoon, they realized we were really and truly going to stay as long as it took, and they basically caved,” Weber says.

Negotiations were straightforward. Every demand was met, much to the organizers’ surprise. In fact, Weber never expected the Women’s Center to become a reality—it was a throwaway demand, designed to be something they were willing to give up during negotiations.

“It was pretty clear the University had to do something,” Sandel says. “There was serious fear and danger, plus a public relations crisis.”

Getting the center off the ground was a “process,” according to Weber, but a process that moved quickly. Housed in Logan Hall (since renamed Claudia Cohen Hall), the PWC became a place for women to connect with each other and engage in activist work.

They also developed educational opportunities, including the Free Women’s School, a ‘courses without credit’ program offering women from Penn and the greater Philadelphia area an education in “areas not usually offered in the college curriculum,” Sandel says.

“A Place I Could Be Myself”

The Penn Women’s Center celebrates five decades of providing advocacy, advising, refuge, counseling, company, and tea. From its origins in the struggle against campus sexual violence, the center has evolved to tackle a range of concerns, from wellness to combating racism. The latest debate: Is its name, meant to be welcoming, too restrictive or exclusionary at a time when gender itself is contested?

On a mild late-summer afternoon, soon after the semester’s start, a purple-and-white banner announcing an open house is attracting both the avid and the merely curious.

“I’m a woman. I like to be in spaces where other women support each other, and that’s obvious when you see the words ‘Women’s Center,’” says Leigh Monistere GrEd’28, a first-year student at the Graduate School of Education. The founder of a literacy nonprofit, she is among a stream of students investigating the Penn Women’s Center, housed in the former Theta Xi fraternity house at the corner of Locust Walk and 37th Street.

On the porch, visitors snag free T-shirts celebrating the center’s 50th anniversary and proclaiming, “Growth. Action. Solidarity.” Inside, they crowd around a table to iron decorative decals onto pouches with the center’s logo.

There’s free food, too: chocolate-covered pretzels in the living room, cheese and fruit in the eco-kitchen, with its energy-efficient appliances, cork floors, and cabinets of reclaimed wood. In the backyard garden students chat with Women’s Center staff over lavender lemonade and iced English breakfast tea. On the patio are chiseled quotes by women writers and other icons of feminism and civil rights. From Alice Walker, author of The Color Purple, comes this gentle observation: “In search of my mother’s garden, I found my own.”

Since 1973, the year of its founding, the Penn Women’s Center—which relocated in 1996from Houston Hall—has been a refuge, gathering place, and resource center for the Penn community, including faculty and staff: women mostly, but also sexual minorities and the gender nonconforming, and sometimes their straight male allies.

“The Penn Women’s Center was also a home for young gay or LGBT students,” says Daren Wade C’88 SW’94, now associate director of career development at the University of Washington’s School of Public Health. “It was very much a place that I felt like I could be myself.”

Mika Rao C’96, who was president of the South Asia Society at Penn, says she relied on the Women’s Center to help a friend with financial problems stay in school. When members of the South Asia Society faced an incident of racial intimidation, “the first thought I had was, ‘Let’s call the Penn Women’s Center,’” says Rao, now managing director of williamsworks, a philanthropy consulting firm. “What I found was that the Women’s Center was just there to support women, period, and [help them] navigate a very large, complex university system.”

Born out of concerns about sexual violence, the center also has provided a locale for a meeting or hangout, a cup of tea, career advice, quiet study, or confidential counseling. Programming over the years has tackled the nuts-and-bolts feminist issues of sexual harassment, pay equity, and reproductive rights, but also wellness and carpentry skills. The center has been at the nexus of University-wide struggles to better the status of both women and minorities, helping to spawn a range of affinity and activist groups. It was intersectional and anti-racist long before the terms became buzzwords.

But much of its agenda wasn’t explicitly political. In recent years, new mothers—including the center’s current director, Elisa C. Foster—could avail themselves of a lactation center. A small crafts room provides yarn, fabric, and a sewing machine. Along with feminist classics, the library offers poetry by Anne Sexton, Jeffrey Eugenides’ novel Middlesex, and the stories of Gertrude Stein. A 2017 volume titled Crafting the Resistance: 35 Projects for Craftivists, Protestors, and Women Who Persist has helped inspire center programming, Foster says.

The Women’s Center’s conference room is temporarily overflowing with stacks of newspaper articles and other documents. In honor of the anniversary, Foster is assembling an archival display that will debut during Homecoming Weekend. Spring semester events will include a joint symposium with the Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies Program [see sidebar] and a May 18 celebration during Alumni Weekend.

The yearlong anniversary also will be an occasion for the Women’s Center to reevaluate its mission—and its name. “Nationally, at universities across the country, their Women’s Centers are changing their names to Gender Equity Centers,” says Foster. “We hear it from the students, we hear from the community that we serve, we hear it from the national trends.” A name change isn’t happening this year, but “it’s not off the table,” Foster says.

Natives at Penn Hosts March on Campus to Celebrate Indigenous People’s Day

Natives at Penn hosted a march on campus to honor Indigenous People’s Day at Penn.

Carrying their tribal nation’s flags, posters, and a Natives at Penn banner, students marched from Gutmann College House to the Starbucks at 34th and Walnut Street beginning at 10 a.m. The march marked the second such celebration on campus since Penn first recognized Indigenous People’s Day in 2021.

“We wanted to have visibility on our day, to show the campus that it’s Indigenous Peoples Day, and there are Indigenous People people still here,” Wharton junior and NAP member Ryly Ziese said. “We had a lot of people from NAP come, and we had also had allies show up and support.”

College junior Mollie Benn, who is a member of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, said that the march aimed to celebrate the identities of Indigenous students.

“In prior years, [the march] had been to raise awareness of Indigenous students, but more importantly, to get the University to acknowledge Indigenous Peoples day,” Benn, who is also a Daily Pennsylvanian multimedia staffer, said.

Vice Provost for Education Karen Detlefsen and Vice Provost for University Life Karu Kozuma sent an email to students on Monday addressing Penn’s commitment to Indigenous students and acknowledging Penn’s location in Lenapehoking, the ancestral and spiritual homeland of the Lenni-Lenape people.

Following the march, Natives at Penn hosted a breakfast at Greenfield Intercultural Center, and some members of the group attended Indigenous People’s Day in Penn Treaty Park in Philadelphia’s Fishtown neighborhood.

Ziese, who attended a tribal boarding school, said she is accustomed to having a holiday from classes for Indigenous People’s Day.

“I usually request or I email all my professors every year, and ask for an excused absence, because it is a cultural holiday for me,” Ziese said. “Usually professors are very welcoming to the idea of having an excused absence.”

This past year, the University allocated Natives at Penn a new space in ARCH. The group has been in communication with Kozuma regarding their plans to utilize the new space, in addition to some issues they are working to resolve. The group is hoping to plan more events to further utilize their ARCH space, although they do not plan to fully relocate from the Greenfield Intercultural Center.

“Our goal this semester is mostly community building, we’ve had to deal a lot with administration and different external issues in the past,” Benn said. “We really just want to focus inward and form closer connections to other members of NAP and new members.”

The club recently recruited a new class of Native first-years at Penn.

“We have more new members than I have ever seen,” Ziese, who has been in the club since her freshman year, said

Weingarten Center’s Ryan Miller, EdD Featured on CBS News

Ryan Miller, Ed.D., Director of Academic Support in University Life’s Weingarten Center for Academic Support & Disability Services, is featured on Pittsburgh’s CBS subsidiary, KDKA-TV sharing tips to maximize time management and avoid becoming overwhelmed.

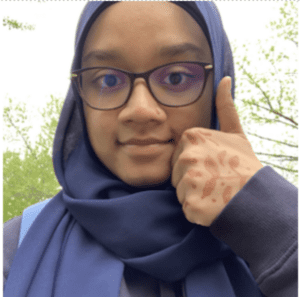

Student Spotlight: Maliha Rhaman

Penn is an institution that prides itself on its diverse student body and it’s no surprise that many students at Penn celebrate Ramadan. To learn more about this sacred holiday, University Life reached out to Maliha Rhaman in hopes that she would share what it looks like to practice Ramadan as a student on-campus. Maliha was gracious enough to share her experience, including what a particular day might look like for a student during the holiday.

This year Ramadan starts on the 22nd of March and ends on the evening of April 21st.

What is Ramadan?

It is the Arabic name for the ninth month in the Islamic calendar. It is regarded as one of the holiest months for Muslims, and it’s characterized by a period of fasting. This is meant to represent one of the five pillars of Islam.

The 5 Pillars of Ramadan Are:

- 1. Faith

- 2. Prayer

- 3. Charity

- 4. Fasting

- 5. Pilgrimage to the Holy City of Mecca

Where are you from?

I’m from Atlantic City, New Jersey

What class are you taking and what are you studying?

I’m a sophomore studying Health and Societies and minoring in Chemistry and Asian American Studies. I am also on the Pre-Med track

Do you have any hobbies you would like to share?

I’m really into K-dramas because since school is so stressful, it’s nice to watch something funny, romantic, and simple. I also like to go on walks, especially by the river.

What is your favorite class you’re taking right now?

Asian American Activism. I like it because it’s my first Asian American Studies class, and I’m learning a lot of history that I didn’t know about. It’s really interesting to learn about Asian Americans in the 1800s and 1900s. Most of us are first-generation American citizens, so it’s really interesting to learn about the people that came here 100 years ago and what they went through. We also have guest speakers who are activists. That is really cool and interesting to experience, especially as a Pre-Med student because it’s so different from the rest of my classes.

What class are you most looking forward to?

Introduction to Asian American History. Since my current class focuses more on activism, I wanted a class that focused on history. It will go more in-depth, and I’m really looking forward to it.

What is your favorite place to eat around campus?

I like to go to Kiwi. I don’t eat out often, but I’m always down for a late-night snack!

When did you first start participating in Ramadan?

I didn’t have to do it until I was 11; however, I started practicing when I was 7. I didn’t do it for the full month, but I did it for a couple of weeks because my brother and my parents were doing it. It was a good habit to practice. At that point, it was August, so if I could get through it in one of the hottest months of the year, then I could definitely get through it afterwards.

How does it make you feel? Do you feel more connected to Allah and to your community by practicing fasting?

I like the community aspect of it, especially at Penn. Ramadan is considered as a time of reflection, forgiveness, and being kind to others and yourself. Definitely listening to lectures about Islam, listening to or reading the Quran. Breaking fast with family brings me closer to God, and that’s why I’m practicing to begin with. Especially at Penn, because there is this greater sense of community with the MSA and that we have iftars five days a week. It’s honestly a little easier being around my Penn community. Growing up I had Muslim friends but they did not practice as much as I did. At Penn, I feel that being around people who practice as much as me or even more has helped me stay on track and continue to be religious.

How has it been navigating through the rituals of Ramadan and being a student at Penn?

I think it’s harder because when you are in high school — yes, you have to be up at 7 a.m. — but it’s not that hard compared to college. At home, my mom would wake me up to eat Suhoor, and now I have to make sure I get as much sleep as possible in order to wake up in time and have a meal before my classes. The meal itself is very different, as my mom would have a slow cooked meal, and here I wake up to eat a granola bar. Taking this in mind, I think sleep has been an issue: not getting enough sleep has made it hard to focus on class and studying for exams has also been difficult. Because of that, I have to study all the time, and I don’t have enough time to devote myself to Islam, read the Quran, or pray in congregation. Activities have also been difficult to maintain because they coincide with breaking my fast. Everyone has been very understanding on why I can’t be present, but it is a little sad that I have to miss out on that part of my Penn experience, especially big activities like Spring Fling.

What is Eid Al-Fitr? How are you planning on celebrating it?

Eid Al-Fitr is the last day of Ramadan where we break our fast. Because I have the privilege of being so close to home, I will go home and spend it with my family. Although there is a community at Penn for me, Eid is about family. Since I recognize I have the privilege of spending it with my family, I try to relish the time I’m home.

Can you tell me what your day during Ramadan looks like?

‘We Bloom Together’ – a mural in the ARCH celebrating Asian Pacific American Heritage Month

From the vivid red poppy of Turkmenistan to the golden shower tree of Thailand, all 66 Asian and Pacific Island countries are now represented on a vivid mural in the ARCH building lobby. The mural, “Planted in Different Worlds by Chance, But We Bloom Together by Choice,” was planned by the Pan-Asian American Community House (PAACH) and unveiled with student collaboration in an April 13 event.

The base of the painted mural is a woman’s silhouette and a house icon representing PAACH, said Vicky Aquino, associate director and self-taught artist. Aquino came up with the mural’s vision. PAACH, she said, “is a place where everyone can grow and bloom like flowers that have their own colors, scents, and unique beauty.”

Aquino invited students to choose one or more of 66 flower decal stickers and attach them to the mural, adorning the hair and neck of the silhouetted woman with roses, lilies, plumerias, and Tahitian gardenias.

“The national flower of the Philippines is jasmine, which smells really good,” said Aquino, who chose that as her sticker. “As a Filipino American, that’s my pride. I really want to be inclusive of every single person; the best way is to represent them through the national flowers of Asia and the Pacific Islands. As a community, we should all work toward the same goal of advocating for each other, uplifting one another, and living our lives harmoniously like a field of colorful flowers.”

Anya Arora, a third-year Wharton School student from Singapore studying finance, and Mary Yao, a fourth-year Wharton student from Longmont, Colorado, studying finance and operations, were excited to see a new mural for Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage (AAPI) month, celebrated in May, and came to place stickers, they said.

“There’s a lot of diversity amongst Asians and Asian Americans,” Yao said. “Everyone has really different backgrounds.” Yao meets with the Asian American Pacific Leadership Initiative, a nonprofit that began through PAACH in 2001. While the students in the group explore their leadership styles through multiculturalism, they also “try to unpack a lot of what that what it means to be Asian American,” Yao said.

Grace Edwards, a second-year studying health and societies with a journalistic writing minor, worked with the PAACH team on the mural as their office assistant intern. Edwards, who grew up in Damascus, Maryland, and has since moved to Haverford, Pennsylvania, felt it was important to include everyone, she said.

Edwards identifies as biracial. Her mother is from Vietnam; her father is from Barbados. Sometimes, she says, she felt as if she had to choose. During the pandemic, there was a surge of both anti-Black racism and Asian hate, she said.

“I was able to come to terms with that and figure out what it means to be Black in America and what it means to be Asian American in America,” Edwards said. “I’m still kind of navigating that. But I’m hoping that I can use my identity to bridge these two cultures.”

The mural also incorporated a QR code that goes to a website where students can list additional AAPI organizations. “If you are part of an AAPI community, please identify that group so that we can come and reach out to you in the fall to collaborate,” said Cindy Au-Kramer, PAACH finance, operations, and program coordinator. “If you are looking to connect and you don’t know what the resources are, whether it’s Penn services, alumni connections, or community partnerships, come to us so that we can connect you.”

This project was supported by the PAACH team and program assistants; Marjan Gartland, director of creative strategy and design at University Life; and Will Atkins, associate vice provost for university life.